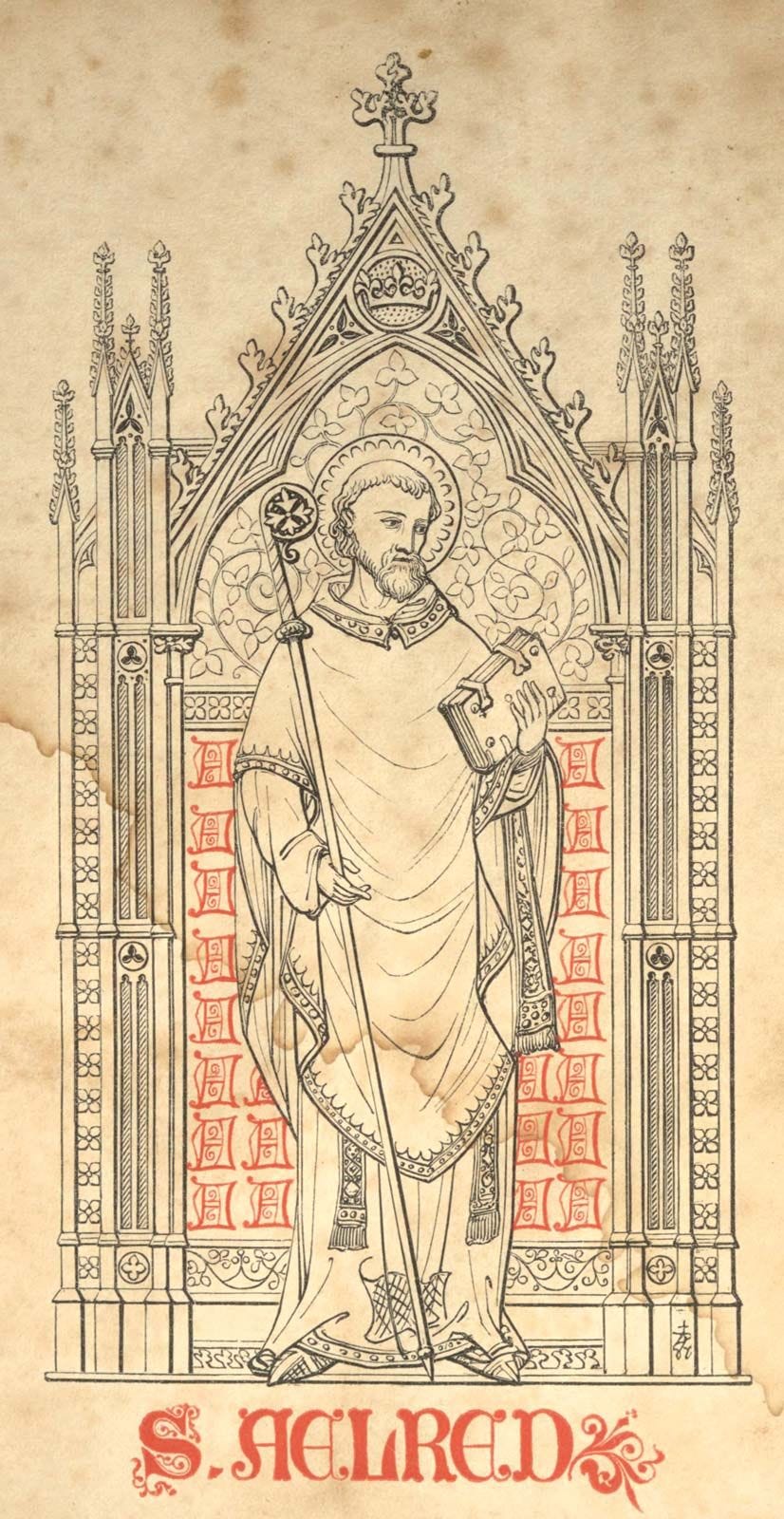

On Befriending Difficult Scriptures

spiritual reading as a form of spiritual friendship

•

When I was still just a lad at school, and the charm of my companions pleased me very much, I gave my whole soul to affection and devoted myself to love amid the ways and vices with which that age is wont to be threatened, so that nothing seemed to me more sweet, nothing more agreeable, nothing more practical, than to love.1

Those are the opening lines o…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Speakeasy Theology to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.