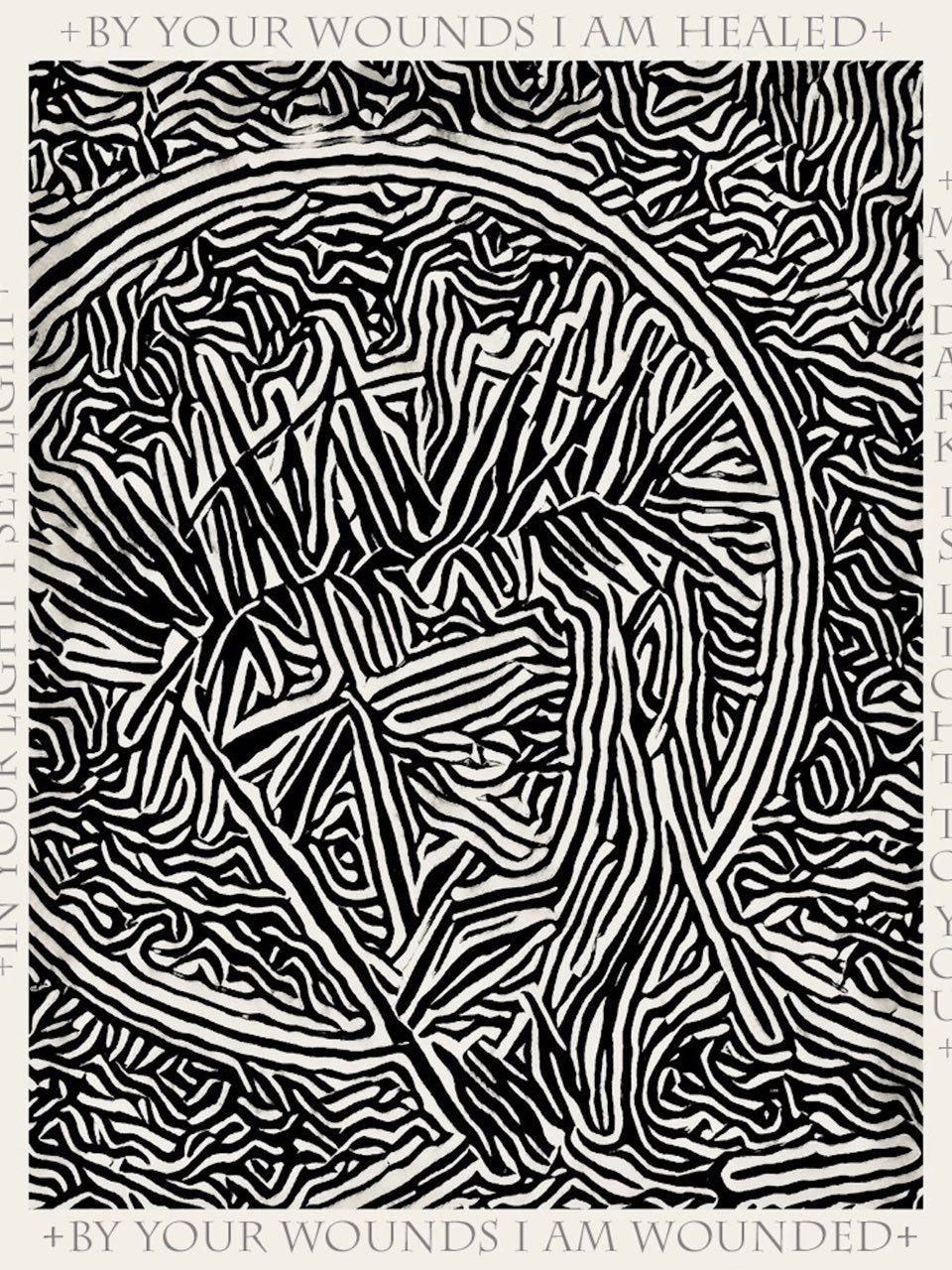

He Does Not Suffer the Fact that He Suffers

God Glorifies Himself in the Human: A Christological Anthology

God Glorifies Himself in the Human: A Christological Anthology

God Glorifies Himself in the Human (Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Christology Lectures)

He is God, He is All Things (Melito of Sardis, On Pascha)

God Could Not Not Save Us (Athanasius, On the Incarnation)

What Happens with Jesus is How God is God (Jenson, Systematics Vol 1)

Thi…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Speakeasy Theology to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.