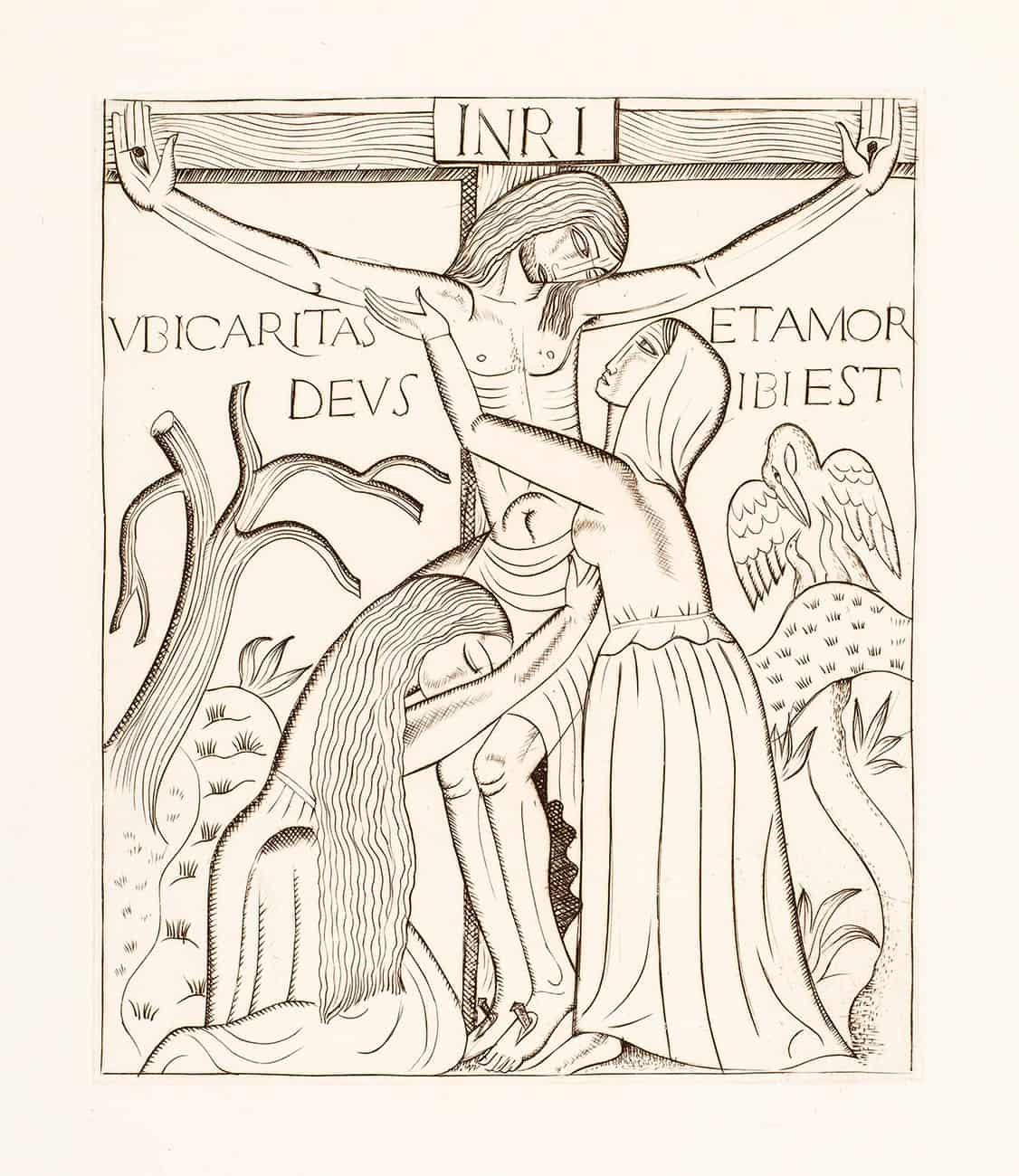

God Glorifies Himself in the Human

God Glorifies Himself in the Human: A Christological Anthology

This is the start of a new series, a Christological anthology, highlighting what I regard as essential passages. I will also offer some brief reflections on the passage, including suggestions for teaching it.

The first entry, which gives the anthology its title, is from Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s 1933 lectures on Christology, …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Speakeasy Theology to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.