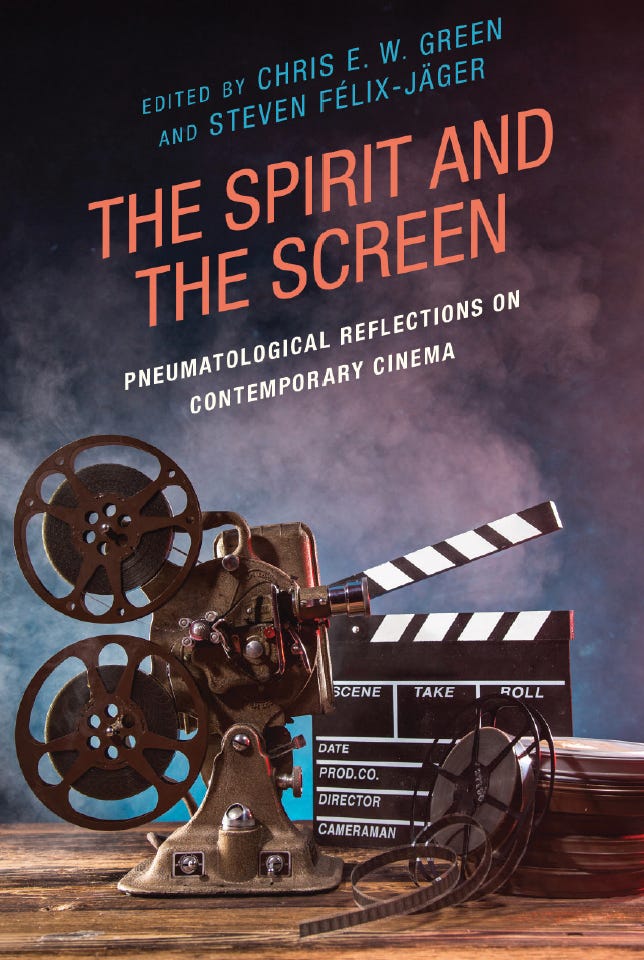

The Spirit and the Screen 2: Austin Kamenicky on the Difference between Christ-Figures and Spirit-Figures

second in a series on pneumatology and cinema

Michael Austin Kamenicky is an independent scholar. His work focuses on the intersection of Pentecostal aesthetics and ethics (and sometimes serpent handling). His writing has been published in the Journal of Pentecostal Theology, the Journal of Religious Ethics, and the edited volume The Performative Ethics of Human Flourishing.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Speakeasy Theology to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.