Sunday’s readings include the story of the Gerasene demoniac. This is a story, one of a set of four (I’ll share the others at some point), that imagines scenes from Jesus’ life from the perspective of a witnessing child. Maybe it can be of some use to those who have to preach the text on Sunday, and some enjoyment for others.

•••

The great drove of swine moved as one vast, breathing thing, a thousand bodies and more heaving with a single mind through the mud they made with their own filth. Swarmed by flies, the kid watched the herd surge ahead of him, their cloven hoofs and leathery snouts rending the earth, their stink rising in waves that made his nostrils burn and his eyes bleed. The heat had turned everything rotten.

Months and months had passed and he hated the work more every day. The worst jobs always fell to him. “Kid,” they’d say, and he would know. His father had told him some hatreds are poisoned cuts, worsening in time. Day into night, the swineherds would trade their lies and banalities, gnawing on them like moldering bread. The kid kept his back to them, nauseated by their peculiar smell, the reek of men who have come to let themselves enjoy making things suffer.

Nothing would grow here for seasons. Wherever the drove and its drovers passed, the land was as good as salted—trees stripped bare, crops ruined, water fouled, native grasses torn out by the roots, leaving nothing to hold the earth. The people of the region cursed the lot of them, to no avail. What were curses to the cursed? Their master grew fat on Rome’s coin. What did he care if the land withered? The war machine was a beast that must be fed.

On the bellies of some in the herd the kid could see marks of wasting disease. Weeping lesions and suppurating sores, ghastly lumps under the flesh, skin peeling away in bloody sheets like fruit overripe. He’d seen such signs before, on those living parables of godforsakenness outside the city gates. Their affliction spoke of judgment, of wrath, and now here it was among the swine, spreading. Each morning, he’d study his own skin in the gray light, expecting the signs of what he knew was coming, corruption spreading to the corrupt.

A sudden cool on the cliffs carrying the musky smell of rain, then a storm erupted over the sea below them, a tempest churning the waters white. A wall of darkness raced toward them across the waves, spears of lightning piercing holes in the sky above. The kid saw in the flashes a few small fishing boats pitched and rolled, already taking on water. He could not help but feel a thrill at the thought of their danger.

Thunder cracked and Fat Thomas jumped and swore, begging mercy. But Sore-Mouth shook his head, picking at the sores that ringed his lips. “Expected,” he said. “Deserved.” “The kid’s fault,” Dead-Eye snickered, and they all laughed, bending their heads against the rain.

Memory crashed over him then in the stinging rain. He saw himself small again, wallowing in stable muck, his older brother’s shadow falling across his upturned face. You pig. The word hadn’t been the wound. Nor even his father’s laugh. It was how well the insult fit, like a lost thing having finally found its owner. Yes, he thought, the world has been trying to teach me this lesson for a long time. Some creatures are made to wallow. A deeper memory stirred in his turbulent depths, asking to surface. He refused it.

Abruptly as it had arrived, the storm died, leaving an eerie quiet in its wake. “Thank God,” Fat Thomas said, though his voice held no gratitude. “No,” Sore-Mouth sneered, working his ruined lips. “Just fattening us up for the kill.”

The hogs loved the kid best, pressing their vile girth against him, hides slick with grime and worse, desperate for his touch like beggar children seeking blessing. Their rheumy eyes reminding him of something he did not know and was afraid to learn. One particularly massive black sow—Cleopatra, he had named her, thinking of a woman from the village who had stirred some forbidden desire—followed him like a shadow, her teats swinging heavy and grotesque.

Sometimes, he found himself kicking out at the hogs or striking them, the way the others did. Afterward, he would feel the burn of the strikes in his palms. Once, he brought his stave down like a hammer on the head of one of the runts, felt the crack of bone beneath. The others had laughed, called him a natural, and wasn’t that the truth of it? What he’d been running from all along? Not the filth but how he took to it. He despised the disgust that rose in his gorge. Despised even more how righteous his cruelty had felt. But that, he figured, was the proof of what he really was.

•••

All noise died, as if the world itself had been strangled. Even the herd fell silent. The kid felt it first in his chest, the tightening, an iron weight, before he saw what the others were seeing, their faces drained of blood.

The ghoul had erupted from the trees behind them, a thing born of nightmare. The kid had heard a hundred stories if he had heard one. How it could not be chained or stocked. How its screams drove the ewes and lambs mad. How it circumcised itself with a stone. How no spell could drive it out. The kid thought the monster looked as if it had been peeled, its nakedness more blasphemous than obscene.

Boats appeared on the shore like a vision, men rising from them and standing above their shadows on the rocks. Behind them, the sea was glass. One figure stood out from the rest, not by height or bulk or dress or bearing but by the way the others moved around him.

Unintentionally, the kid had edged down the embankment, Cleopatra and her ridiculous court trailing behind him like a fool’s triumph. He found himself near enough to see the demoniac's eyes. He wished he hadn’t. But the madman paid him no mind, fixed on the still figure among the fishermen by their boats, as if the rest of the world had burned away. The ragged sound that came from him was the sound of a soul being rendered, not breathing so much as acting on the memory of breathing.

“What is your name?” The stranger’s voice was quiet but clear. Just a question, gentle as a nuzzle. “My name?” The voice that came from the wild man wasn’t a proper voice at all. “My name...” “What is your name?” The sufferer’s face contorted again, became almost recognizable: “I am... I was...” His mouth worked like he was choking. The air around him thinned, his eyes rolling back in his head. “We are Legion!” An explosion of sound, a thousand voices pouring impossibly from a single mouth like the rush of hornets from a struck nest. “Have you come to torment us?” The voices asked, their noise terrible. Then, begging, pleading: “Don’t send us back.”

All around them now the hogs had gathered in great snorting circles of hairy, muddy hides, orbiting at various depths the opposed figures like dark moons. “What is your name?” The healer spoke to the tormented one like he was talking to a spooked horse or a lost child. The possessed man’s lips opened like a wound and when sound came, it was hoarse, broken, barely audible. The kid's heart seized—it was his own name, the one he’d buried when he joined the drovers. The sound of it now, torn from this tormented stranger’s throat, made him stagger. Did so many voices live in him too?

“Send ‘em into the pigs,” Sore-Mouth said with inspired spite. “Yes. Let us,” the Legion hissed, bargaining, desperate. The healer tilted his head and sighed like an annoyed mother, and commanded them with a wave: “Out.”

There seemed at first no change in the man possessed. He remained standing straight as a spear, fists tight at his side, almost expressionless. Then one by one the pigs’ eyes emptied and the herd began to move. The kid’s gut twisted. “No!” The word ripped from him too late. Cleopatra’s grunt had become something unrecognizable, a sound at war with meaning. Others were making the same unearthly rattle, the same dry cough. The kid called out and his hand reached but grasped only air. The drove was moving again as one, pressed by a terrible purpose. The earth trembled beneath them, their hides iridescent with unholy light, ears and tails flapping like absurd battle pennants. The kid watched in horror as they stampeded in rank toward the precipice. He spotted Cleopatra in the surge, her bulk unmistakable. He could not bear to look or to look away. A massive boar tumbled over first, followed immediately by another and then others. A dozen followed after them, their legs wheeling in the empty air. Then the whole company was pouring over the edge, hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of shrieking, flailing forms cascading down the cliff face, a river of unclean flesh stretching from sky to sea. The waters received them with eruptions of spray, the foam turning first pink, then crimson, then purple as wine.

Blind with fury, the kid lurched toward the healer, screaming threats, the prod a hammer in his hand. “I will kill you!” But the earth betrayed him, his feet losing purchase on the ground, and he fell headlong into the gravel, his weapon skittering away ridiculously.

The healer’s hands found him, lifted him. They were gentle hands. Lifted him as a mother lifts a little child who’s awakened in the dark and is afraid. Looking up, bracing for rebuke, the kid found instead a laugh in the healer’s eyes, a secret too good not to keep. That same something stirred in his depths, deeper even than what he had been afraid to recall it. And behind the healer the kid could see the man, at last himself, bent quietly in a cleansing grief, wrapped in a borrowed cloak and the wonder at finding himself free.

•••

Years and years pass. And more years. Now an old man, the kid stands again above the sea that swallowed the drove, remembering. Villages burn in the mountains behind him, Vespasian’s legions moving like a plague of locusts through the region, answering rebellion with iron and fire, fulfilling Rome’s promise of peace.

He remembers his return home, now far in the past. His father in the courtyard in the early evening working at some repair, looking up, the hammer shaking in his hand like a winged bird, to see his lost son standing at the gate. He sets the tool down carefully, as if it might break, and they embrace. That is all. It is more than enough. Late that night, his brother, who had for so long nursed his contempt, brings wine, good wine he’d been saving, and pours cups for the three of them. After a long talk and stories of the far country, they sit at the table in a silence that feels different from any silence they have ever shared.

He remembers all the years following the healer and his friend, the one once called Legion, teaching him the way. He remembers how when word came from Jerusalem about Jesus’ death, they had wept but not despaired. “He drew poison from the world,” his healed brother had said. Later, when the good news reached them and they spoke again with the fishermen they had first met that day by the calmed sea, they had wept again, this time with joy.

As an old man, a dying man, he finally understands what he witnessed so stupidly at first as a kid. He knows what sent the hogs to their death, what it was that made the rulers send the Lord away. The truth is more frightening than any terror to those who profit from slavery and war. “Better the devils you know,” they had said. The herd, those holy swine, had in their mad rush to destruction become the willing instruments of God, collaborating with nature and the Lord of nature against the unnatural. Such jests God plays with empires. What we do to ourselves is nothing compared to what the Lord of Hosts and the hosts of the Lord do for us.

Today, in the haze of the fires, the old man watches young soldiers march through the valley like a single body, armor glinting red. They march beneath wings of gold, bearing their gods on poles not knowing they themselves are the sacrifice. His heart breaks and he does not try to keep his heart from breaking. These same boys, he knows, will wake in nights years hence, haunted by what they have done, by what they have let be done, by what they have become, by what they find missing from their souls.

How much mercy there will be in that haunting.

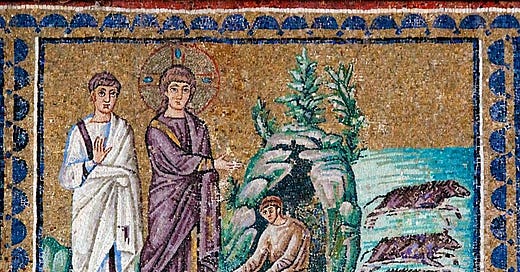

![[object Object] [object Object]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!4-0U!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ffe9a3da2-25a1-42e4-a347-fd8866ffda85_875x637.jpeg)

Goodness. The tie you made between this story and the prodigal son broke me open. I have no other words but to say thank you for sharing this.

Wow. This is beautifully written. Wow. So vivid and alive. Thank you so much for sharing this with us.