O Lord, my heart is not lifted up;

my eyes are not raised too high;

I do not occupy myself with things

too great and too marvelous for me.

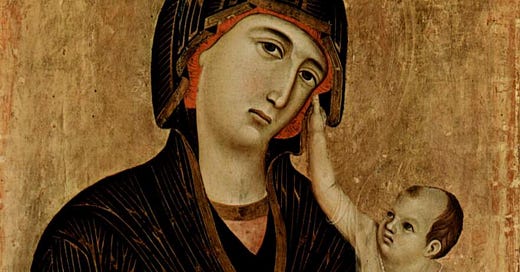

2But I have calmed and quieted my soul,

like a weaned child with its mother;

my soul is like the weaned child that is with me.

3 O Israel, hope in the Lord

from this time on and forevermore.

We’re tempted …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Speakeasy Theology to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.