Cormac McCarthy died on Tuesday. Last December, I read James Wood’s New Yorker review of what turned out, as expected, to be McCarthy’s last works: the sibling novels The Passenger and Stella Maris.

I didn’t like it much, but there were, as always with Wood, a number of impressively-crafted lines, interesting in their own right, and a few sharp insights into the workings of McCarthy’s fiction.

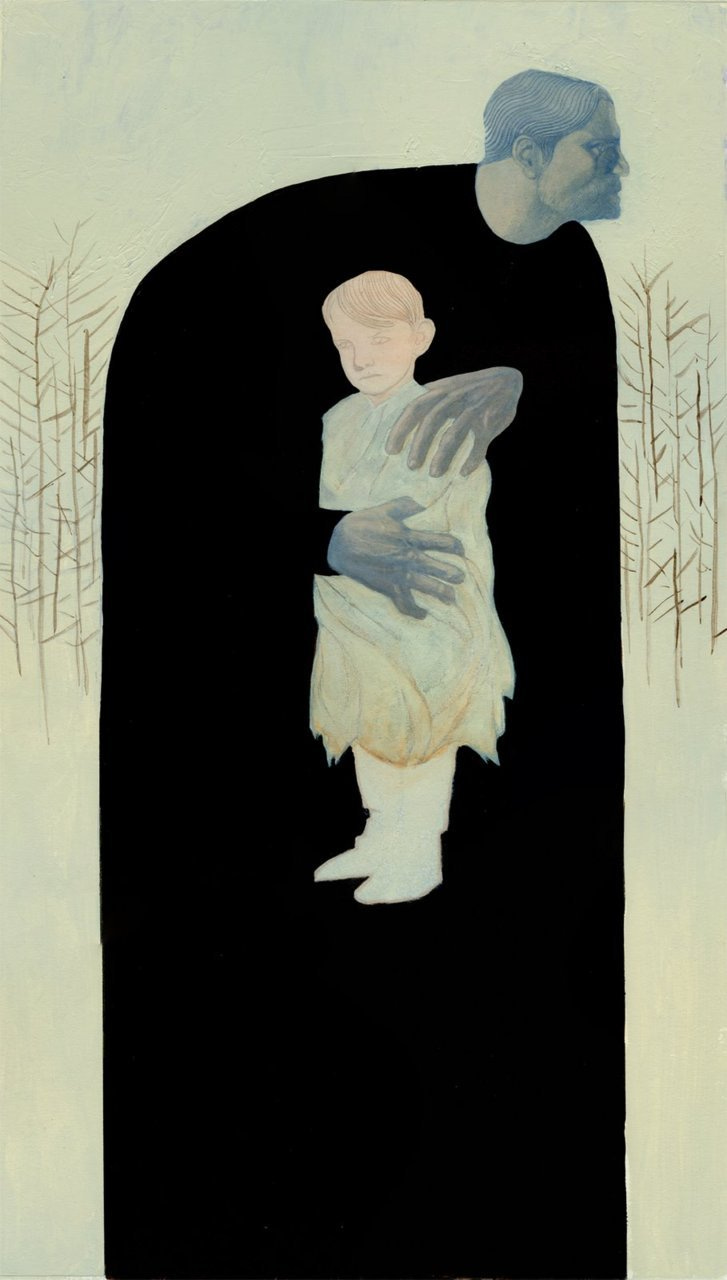

One in particular has stayed with me. For reasons the novel never quite discloses, the protagonist of The Passenger, Bobby Western (the name matters, though not exactly in the way I would’ve guessed) is hounded and harassed by nasty government figures. But what actually moves him, Wood says, is “the grief he feels at the loss of his sister, by the dubious legacy of his father’s work, and by that theological woundedness shared by so many McCarthy heroes.”

Wood may be sneering, but he’s not wrong. And what he says of McCarthy’s characters is no less true of McCarthy’s readers. We doubting Thomas types are drawn to these stories because we need to touch the wounds we fear God has left in the world, if only by his absence, and because we need a trustworthy doubter to finger our scars, assuring us that they are in fact signs of good faith.

Wednesday, Brian Phillips, in his memorializing of McCarthy, which doubled as a lament for a dying breed, related a conversation he had twenty yeas ago with a theologically-wounded friend:

“The total immanence of the created world.” That’s what a friend of mine called the object of McCarthy’s vision. It was 2005 or 2006. We were sitting in a Friendly’s in North Haven, Connecticut, talking about Blood Meridian; or, The Evening Redness in the West, the 1985 novel that’s sometimes considered McCarthy’s masterwork. My friend, who was serious and religious, was trying to explain the Christian theology he could detect in McCarthy’s novel. I, a light-minded person, temperamentally casual about the problem of total immanence, was trying unsuccessfully to drink an Oreo milkshake through a straw. My friend said, “He’ll write 10 pages describing the landscape and then some act of horrific violence will come out of nowhere and he’ll cover it in one short paragraph. And then he’ll go back to describing the landscape, and the whole time the tone will stay exactly the same, the tone won’t change at all, because if God created the world, then everything in the world is equally suffused with God’s presence. A headless corpse is as much an aspect of God as a cloudburst or a sleeping child. I realized at this moment that I was going to have to switch to a spoon. I fumbled with the plastic wrapper. My friend said, “It brings the paradox of faith to this unbelievably intense crisis point. The absolute indifference of the universe is a sign of the absolute fullness of God’s presence.”

Wood is exasperated by what he takes to be McCarthy’s coy theologizing. In fact, what he likes best about the final novels is their difference on this score from all the works that came before them. They “flush McCarthy out of his rhetorical cover,” exposing McCarthy, finally, as every bit the Gnostic pessimist Alicia is. (Alicia is Bobby’s sister, and the protagonist of the second novel, Stella Maris; her name matters too.) “The new and welcome thing” in these works, according to Wood, is “the lucidity of the bitter metaphysics.”

McCarthy’s earlier books were so shrouded in obscurity, rang with so much hieratic shrieking and waving, that it was perfectly possible to extract five contradictory theological ideas at once from their fiery depths. That was why “The Road” could be read as both Beckettian pessimism and last-ditch Christian optimism, with its orphaned little boy left, at the end, to carry with him the light of the divine and the flame of the human. Can the world be repaired or not? Is it divinely intelligent or not? These new novels flush McCarthy out of his rhetorical cover, and his decidedly austere and unillusioned answer to both of these questions is no.

Again, sneering—but not too far from the truth. Theologians do typically find their own deepest convictions in McCarthy’s works. I certainly did. Perhaps Brian’s friend did as well. And given that “Advent begins in the dark” is one of Fleming Rutledge’s signature lines, is anyone surprised that she loves McCarthy?

Still, even if theologians find McCarthy’s fiction mirroring back to them their own convictions, Wood is wrong to think that that exposes some weakness or failure in the novelist’s style. Rutledge is right (dead right, you might say): McCarthy’s writing is biblical, not merely thematically and formally but effectually. Reading him does something to the reader eerily similar to what the Old Testament does.

Yair Zakovitch, Emeritus Professor of Hebrew Bible at Hebrew University of Jerusalem, sums up the whole “historiographic complex” of Israel’s Scriptures, the complex that opens with Genesis’ account of the creation of the world and closes at the end of Kings with Israel’s exile into Babylon, as “a sad story—notwithstanding the faint light that flickers at the end…” Here is the paragraph that follows that claim:

The central message of this huge complex, which reached its final form more or less during the Babylonian exile, is etiological-theological: it sets forth an explanation of God’s resolve to exile Israel, his chosen people and the nation he favored, from its land, justifying the exile as punishment for the Israelites' deplorable behavior. The doctrine of divine justice, of reward and punishment (mostly punishment), is the thread on which are strung all the events that, together, comprise the story of Israel’s history. We find this doctrine being played out already in the complex’s opening stories (Genesis 1-11), stories that tell of humankind’s history before the Israelite nation stepped onto the stage of history: Adam and Eve’s expulsion from Eden, the Flood, the scattering of the tower-builders of Babel—each a result of humanity’s transgressions, and all recounted for the purpose of Israel learning from the bitter experiences of those early generations that sinned and were punished so as not to repeat their errors. But the hope is in vain, and by the narrative’s end the people of Israel are expelled, just as were Adam and Eve from the Garden, and just as the builders of the Tower were scattered throughout the world. Each and every figure in history’s relay-race—from Abraham on, till the last of the kings—is found to be morally flawed.

“The hope is in vain…” Not all hope, surely. But the hope, the one the characters in the stories, even the godly ones, are setting their store by. That hope is vain. Israel is forced to believe that God never fails to keep his promises. But she also knows that God’s faithfulness is never not in question and that the ultimate fulfillment of God’s promises simply cannot happen in time.

As I suggested in the essay I wrote on The Road, the endings and codas in McCarthy’s novels are especially significant, theologically speaking, because it is there that the crucial (!) difference between hope and hope comes into starkest relief. This is true for most if not all of the first novels (including even Outer Dark). And it is true for these last novels—but in a new way. Stella Maris, which consists entirely of dialog between Alicia and her psychotherapist, was released later than The Passenger. And the ending of that novel, like its beginning, is, well, pretty damn Gnostic and pretty damn pessimistic.

Near the end of her story, Alicia says, “The first rule of the world is that everything vanishes forever. To the extent that you refuse to accept that then you are living in a fantasy.” She’s right, of course. The violence of that truth is precisely what’s left us most deeply wounded. Still, it is telling that her final words to her therapist are a request—a kind of prayer, which is for her as for us a proof of life for faith (if not also for the God we, as creatures of faith, can’t help but reach for).

I think our time is up.

I know.

Hold my hand.

Hold your hand?

Yes. I want you to.

All right. Why?

Because that’s what people do when they’re waiting for the end of

something.What end is Alicia waiting for? We can answer that question only if we answer another: Why is this what people do when there’s nothing left to do?

Joy Williams, in her review of the sibling novels, describes Bobby and Alicia as “an Adam and Eve twice banished… soon to be absent forever.” But what if Alicia is waiting in a way she cannot even name for an end she knows deep down she cannot give herself? She tells Dr Cohen at one point that “faith is an uncertain business.” But later she identifies it as “the one indispensable gift.”

The Road ends as it began with the unnamed father lying awake in the dark, steadying himself for death. The Passenger ends with Bobby enclosing himself in that same dark—and reclining into it. Somehow, in spite of everything (or in thankfulness for it), the last of his thoughts allow—no more, no less—for something like hope to continue to flicker and smoke:

Finally he leaned and cupped his hand to the glass chimney and blew out the lamp and lay back in the dark. He knew that on the day of his death he would see her face and he could hope to carry that beauty into the darkness with him, the last pagan on earth, singing softly upon his pallet in an unknown tongue.

A sad story, as any authentically biblical story must be. And Cormac’s now done more than write such a narrative. But who knows what secret fire burns in the song only the dying sing, always in that unknown tongue?

Few statements in all the books I’ve read and all the sermons I’ve heard were as gripping, humbling or convicting as McCarthy’s line after introducing the despicable Lester Ballard: “A child of God much like yourself perhaps.”

Thank you for this tribute to Cormac. A singular voice, an irrefutable talent but most of all a voice of lament in an era of obfuscation and false glamour. His work will prove more timeless than Dickens, more provocative than Huxley.

Chris, exactly before receiving this blog post I literally just read the following excerpt from McCarthy’s, The Crossing, in a FB post, and found myself thinking, “It just needs the heading, ‘The Kingdom of God is like...’”

“There is but one world and everything that is imaginable is necessary to it. For this world also which seems to us a thing of stone and flower and blood is not a thing at all but is a tale. And all in it is a tale and each tale the sum of all lesser tales and yet these are also the selfsame tale and contain as well all else within them. So everything is necessary. Every least thing. This is the hard lesson. Nothing can be dispensed with. Nothing despised. Because the seams are hid from us, you see. The joinery. The way in which the world is made. We have no way to know what could be taken away. What omitted. We have no way to tell what might stand and what might fall. And those seams that are hid from us are of course in the tale itself and the tale has no abode or place of beind except in the telling only and there it lives and makes its home and therefore we can never be done with the telling. Of the telling there is no end. And . . . in whatever . . . place by whatever . . . name or by no name at all . . . all tales are one. Rightly heard all tales are one.”